In China, Even Movie Stars Just Want a Stable Gig

When Jackson Yee, an A-list actor and pop star with 90 million followers on Weibo, decided to apply for a position with the state-run National Theater of China, he probably didn’t expect to find himself embroiled in the biggest controversy of his career.

The application itself went smoothly. On July 6, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security posted the list of successful applicants on its website. Seven actors made the cut. Yee, a recent graduate of the prestigious Central Academy of Drama, appeared at the top, followed by fellow twentysomething stars Luo Yizhou and Hu Xianxu. The other four actors selected were more traditional candidates for the post, which was intended for young performers fresh out of university with no formal working experience.

The initial response to the news, led by Yee’s fans, was bemusement. The National Theater of China is known for productions of classic plays or works of Communist Party history, making it a somewhat puzzling fit for the former TFBoy. Some joked that Yee had applied for the bianzhi — a stable job with lifetime benefits working for a government or government-backed institution. On microblogging platform Weibo, a topic featuring Yee’s name and the popular buzzword “public sector boyfriend” began trending.

But the initial amusement at the news soon gave way to anger, as public opinion turned on Yee, and to a lesser extent, Luo and Hu. Much of that backlash focused on Yee’s qualifications and whether the three may have broken the National Theater’s rules on formal employment during university. But it quickly became clear that critics’ real problem had less to with the application process than the application itself. Why, with youth unemployment nearing 20% and stable jobs seemingly scarcer than ever, did one of China’s most bankable stars feel the need to take a precious public sector position — and the valuable bianzhi slot that comes with it — from a young actor?

There are two types of bianzhi positions in China. The first are administrative jobs in government departments that can only be obtained by taking the civil service exam. That would likely have been a non-starter for Yee. With the economy slowing, the test has become prohibitively competitive as millions of young Chinese long for the relative stability of civil service work. Last November, 1.42 million people competed for just 32,100 jobs, according to Xinhua.

The other type of bianzhi is awarded to select employees of public institutions. These are typically organizations created by state bodies or using state-owned assets for the purpose of promoting social welfare, and are concentrated in sectors like education, science, technology, medicine, and culture. As a national-level art troupe under the direct control of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the National Theater of China is one such bianzhi institution.

Unlike the unified civil service exam, public institutions generally have greater latitude to set their own standards for recruitment. That doesn’t make them any less competitive, however, especially in a poor job market. In the first half of 2022, the surveyed urban unemployment rate reached 5.5%. Unemployment is at 19.3% in the 16-24 age group. Meanwhile, a record 10.76 million graduates entered the job market this year, leading some media to dub it “the hardest graduation season in history.”

Thirty years ago, the buzzword was xiahai, or “plunging into the sea” of private enterprise. Today, everyone seems to be scrambling to make it back to the beach. Although salaries for public sector positions remain low, they offer stability and respectability. Online, people joke that “at the end of the universe, there is bianzhi.” Women claim to want a “public sector boyfriend.” Even the plain windbreakers and white shirts favored by Chinese public officials are having a moment.

At a time when a bianzhi seems like the only safe choice, the sight of coveted positions being snatched away by wealthy celebrities proved intolerable. This shift in attitudes, rather than any misconduct in the application process, is why Jackson Yee’s admission into the National Theater caused such an uproar.

Indeed, other celebrities have joined the state system in recent years without arousing controversy. As recently as 2020, the well-known actor Liu Haoran joined the China Coal Mine Art Troupe without incident. Even just two decades ago, getting a bianzhi was a sign of a celebrity’s star was on the wane. Ji Minjia, a singer who came fifth on the popular variety show “Super Girl” in 2005, joined a song and dance art troupe under the umbrella of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force in 2008. Her decision was hailed at the time as a wise move, since she was less popular than the other four in the show’s top five.

In the face of widespread public opposition, Yee announced on July 17 that he would not join the National Theater. In his statement, he said he had applied for the role out of a “desire to enter the hallowed halls of Chinese theater, to improve and make explorations.” He also emphasized that he had “fully complied with the National Theater’s recruitment and examination requirements” throughout the application process, had not taken any shortcuts, and that the gossip and speculation had left him feeling “extremely uneasy.”

On some level, I can sympathize with his predicament. Although it may seem like he’s on top of the entertainment world, there are plenty of reasons beyond “improving oneself” why an A-lister might find a bianzhi attractive. China’s film and television industries are struggling, with 160,000 film enterprises shuttering in the past three years alone. Actors have seen their careers dry up due to legal troubles or personal scandals. Fan Bingbing, once one of China’s most bankable stars, vanished from public view almost overnight after a tax scandal. For Yee, entering the public sector promises a sense of security, even if the pay is low and the duties onerous.

Film and TV stars may enjoy fame and wealth, but their privileges are more brittle than critics care to admit. In that sense, Yee shares many of the same feelings of insecurity experienced by his peers: Everyone, star and fan alike, is just trying to make it safely ashore.

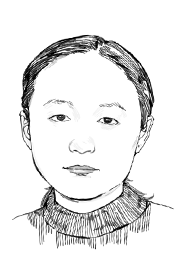

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Jackson Yee poses for a photo, 2021. VCG)